Today’s learning and development professionals face complex challenges such as reduced budgets, an employee base that is spread out further than ever before, and limited time for employees to dedicate to L&D.

The pandemic was a significant disrupter for many. In health care specifically, it necessitated a “command and control” leadership style to maintain an appropriate focus on demanding patient care challenges. Additionally, high patient demand and ongoing staffing concerns resulted in a limited focus on leadership development. This created a concern about a potential gap in the talent pipeline and required us to respond quickly to upskill newer leaders and shift back toward participative and coaching leadership styles, which had previously contributed to our organization’s success.

Well-known for its national and international presence, our organization has a structure that includes a regional health system that branches out from the main campus to serve small communities across four geographical regions covering three states. While part of the same larger health system, these four regions function separately and have differing needs. Strategically, executive leadership is striving to create a more unified system among the four regions and build the talent pipeline to drive the organizational strategy forward.

Specific objectives were to prepare the frontline leader for elevated capabilities to help them include more strategic thinking into their strong operational focus, leverage strengths in themselves and their teams, develop a coach-like style of leadership and develop the confidence to take calculated risks.

From a program design perspective, there needed to be a method that moved significant numbers of leaders through the program quickly, minimized time away from the work unit and fostered relationships between the regions. This challenged us to reshape our traditional classroom learning and adapt it to an approach that allowed for flexibility, networking and self-directed learning for busy frontline leaders.

Our learning design centered on four key approaches: hybrid delivery, peer group discussions, self-directed learning, and a summative synthesis of learning utilizing a capstone presentation.

Hybrid delivery

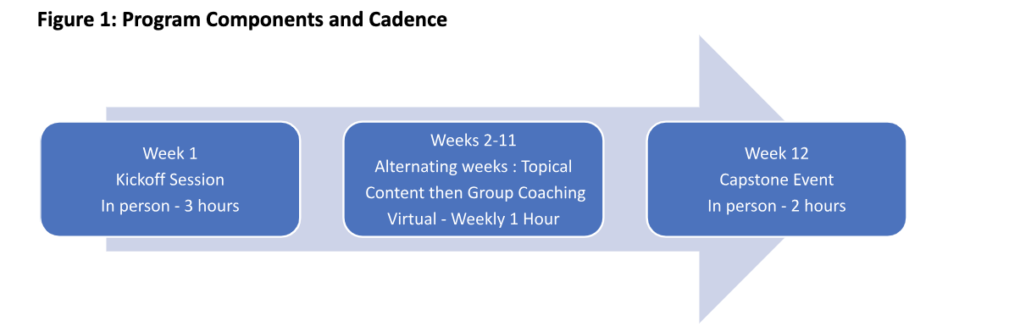

The program design included weekly sessions over a three-month period. The executive leadership sponsoring the program stressed their desire to minimize the leaders’ time away from the clinical practice and to keep participant travel to a minimum. At the same time, they wanted to foster cross-regional networking. The geographical distribution of the four regions posed an interesting challenge in meeting their expectations.

Recognizing the importance and desire of in-person events in a post-COVID era, the facilitators traveled (rather than the participants) to each region in a one-week period to conduct the opening and closing capstone sessions in person. This allowed for networking within the region and provided the opportunity for the local senior leadership to attend and communicate the importance of the program and their commitment to support.

The remaining 10 sessions were held virtually, and alternated weekly between a luminary session (i.e., content delivery) and structured group discussions. (See Figure 1). The participants were also assigned to a cohort of five to six people with cross-regional representation to create smaller communities of learning, promote networking and foster relationships.

The hybrid design allowed for a large number of participants to be enrolled in the program and fostered new relationships within and across regions. Additionally, this approach engaged senior leaders locally and met the goal of minimizing time away from work.

Leveraging peer groups for learning

Learning with and from other people is a key component of how adults learn. To achieve this, we leveraged peer group learning sessions nestled in between luminary sessions. This allowed participants to take the learning from the luminary session, try it in their work and then come back to discuss and learn with and from others in their small group around the topic. Groups were given guidelines for the discussion. A key outcome of the peer group discussions was the sharing of best practices, creating efficiencies in the larger health system and building broader networks.

We observed that the quality of the dialogue within each peer group was dependant on the commitment or ability to attend the session and the level of engagement of the participants. In the future, we would consider a larger group size of seven to nine participants per group and build in more accountability for attendance and participation.

Self-directed learning

During the opening session, program commitments and expectations of the participants were reviewed. We emphasized that each participant was in control of how much effort they put into the learning experience. Recognizing we had learners with a wide range of experience from new to seasoned leaders, self-directed learning approaches were used to allow the participants to tailor the content to their individual learning needs, complete the assignments at their own pace and capture their learning throughout the program.

Weekly virtual sessions were 60 minutes in length and designed to be as engaging as possible. Pre-work (e.g., readings, videos, self-assessments) prior to the sessions reduced the need for didactic content. The luminary speaker was prompted to focus on no more than three key points. This allowed more time during the sessions for participants’ questions and learning activities such as case study reviews and break-out discussions. Post-session assignments created the opportunity to apply new learning to the participants’ daily work. Using pre- and post-session assignments also created accountability as the participants knew they were expected to discuss what they learned with a small group of their peers.

Another aspect of self-directed learning leveraged the use of journaling and reflection. These are powerful methods to strengthen learning, deepen personal insights, and promote the transfer of new knowledge from working memory to long-term memory. Participants were encouraged to keep a journal throughout the 12-week experience and were provided specific reflection questions or assignments throughout the program. This provided a solid foundation of reflections to use in preparation for the capstone session.

Synthesizing the learning

For the capstone event, held in person at each region, participants were asked to create a reflection poster depicting their growth in the areas of elevated skills, organizational leadership capabilities, personal impact and future goals. They presented their poster to their co-participants and their direct leader. The experience was intended to give the participants an opportunity to synthesize the entire 12-week learning experience and to see their growth over time.

For many, this provided a new learning opportunity to present formally to others and build confidence in the skill of presenting. Additionally, they expressed how they appreciated hearing how everyone learns. While there were several themes in the expressed learning, there was also a wide variety of learning insights and new knowledge gained depending on the individual’s degree of leadership experience and the unique challenges in their work environment.

Evaluation

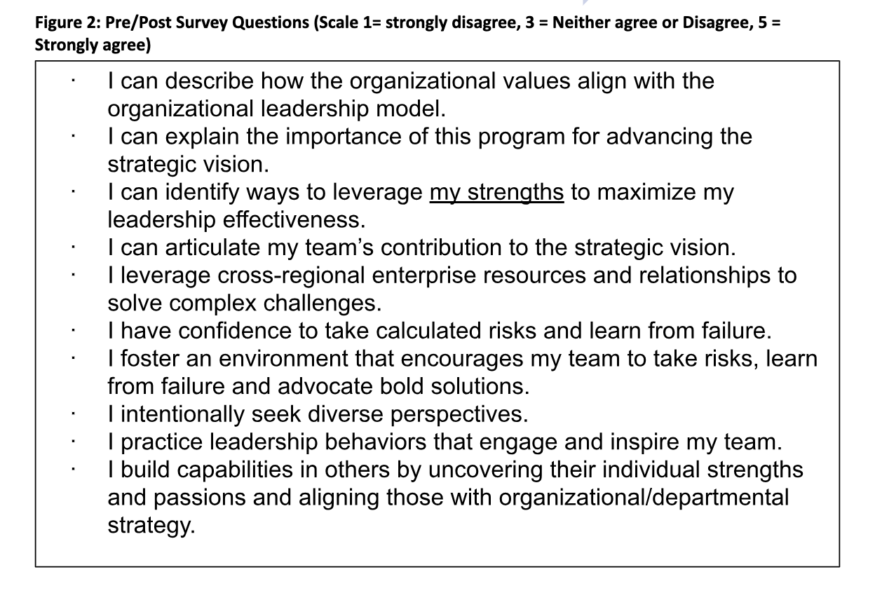

To evaluate the effectiveness of this program, we used formative and summative assessments. Prior to the course, we administered a pre-survey to assess their current level of knowledge and awareness of the concepts we would be discussing over the course of the program. The questions were aligned with each learning objective. At the midpoint of the program, we conducted a short pulse survey to understand how well the format was working. This was valuable and led to minor adjustments in the remainder of the course. Finally, they completed a post-program survey that included the same questions as the pre-survey to assess perceived changes in skills, knowledge and attitude based on learning objectives (see Figure 2).

Overall, the results were very favorable. Ninety-seven percent of survey respondents felt the program supported their leadership development and would recommend the program to others. While we didn’t have matched responses from the pre-survey to the post-survey, the results demonstrated significant improvement in their perceived level of knowledge, confidence and practice of leadership behaviors we were targeting (Figure 3).

Below are a few comments from some of the participants:

- “I have taken many different leadership courses and have attended other webinars and lectures. I felt like the design of this program allowed me to retain the information better than any of the others. Having the peer-based cohorts held me accountable and has made me much more conscious of my leadership abilities and inabilities.”

- “I really enjoyed this opportunity that was given to me. I feel more confident in my abilities as a leader and am able to use the tools I gained both personally and professionally.”

- “This was a great course and I appreciate all that we learned! There are some great skills I picked up that I hope to practice and refine. I’m glad that I have the resources to refer back to, and my capstone poster in my office to keep me centered!!“

- “It was great to look back on my thoughts throughout the program. Journaling was key. Very much enjoyed the engagement throughout this course.”

Conclusions

The approaches we took were an effective way to meet the needs of this specific audience. The participants demonstrated engagement and commitment to learning. It allowed a large number of leaders across regions to build skills and confidence in a safe space while networking and supporting each other. Ultimately, it has enhanced the leadership talent pipeline while minimizing time away from the work environment.

As the work environment and learner needs continue to shift, L&D approaches need to be adaptable and designed to meet individuals where they are and align with organizational needs. Thus, as L&D professionals it is critical that we continue to challenge ourselves to think and design differently.