For the past decade, forces such as global competition, developments in technology, greater job specialization and a rise in knowledge-based industries have been driving the need for a more educated workforce.

HR professionals believe this is only the beginning. The need for skilled workers is not expected to abate but rather continue to increase in the years ahead. These developments will put chief learning officers and all learning professionals at the center of business strategy, especially if skills shortages begin to have a major impact on the bottom line.

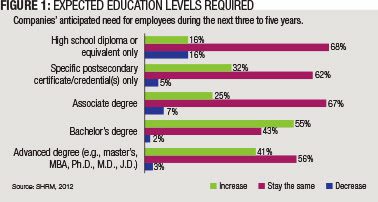

Educational qualifications are expected to rise in the next three to five years across all job categories, according to a joint survey from the Society for Human Resource Management, or SHRM, and Achieve, a nonprofit organization focused on preparing young people for postsecondary education, work and citizenship, which surveyed 4,695 HR professionals. (Editor’s note: The authors work for SHRM). Released late last year, the “Future of the U.S. Workforce” survey shows that in the next three to five years, organizations across industries are most likely to report an increased need for employees who hold a bachelor’s degree (55 percent), an advanced degree such as a master’s, MBA, Ph.D., M.D. or J.D. (41 percent), and specific postsecondary certificates or credentials (32 percent) as shown in Figure 1.

HR professionals cite several key changes in the past decade that are affecting the hiring landscape of today and are expected to impact it even more in the next three to five years:

• Increased staff size (53 percent).

• Increased number of jobs with specific technical requirements (51 percent).

• Higher education level requirements for most jobs (46 percent).

• Increased employee diversity (45 percent).

• Fewer entry-level jobs (31 percent).

The key areas underscore competition for jobs, the need for skilled job candidates and higher skills requirements for entry-level jobs just to get a foot in the door. The industries most likely to report that higher education levels are required today compared with a decade ago are: health (54 percent); manufacturing (52 percent); state and local government (48 percent); and federal government (46 percent).

The industries most likely to report that more of their jobs today demand specific technical skills compared with requirements a decade ago include: high-tech (73 percent); manufacturing (56 percent); construction, mining, oil and gas (56 percent); state and local government (53 percent); and health (51 percent).

The education rates for younger generations entering the workforce may not be enough to meet the demand HR professionals are expecting in the years ahead. As a result, CLOs and other learning professionals will have to help employees obtain the necessary skills and education. Learning and training leaders also will need to specify the technical skills required for specific jobs and to proactively work with local education providers to develop certifications, degree programs, curriculum and classes that meet these needs.

Today’s Education Needs

One reason many organizations are only now beginning to focus on future workforce skills needs is that the ongoing impact of the recession and subsequent weak jobs recovery has resulted in a greater selection of applicants. This may give some business leaders and hiring managers a false sense of security. The survey results indicate that today in organizations across all industries employees generally have educational credentials that are a good match for the job they hold.

However, the picture shifts when looking at the newest hires. The survey asked, “For current job openings that require a minimum of a high school diploma or equivalent, how often are the newly hired employees’ education credentials actually higher than the minimum education listed in the job announcement?” Here, a slim majority of organizations (53 percent) said “some of the time” and slightly less than one-third (30 percent) said “most of the time.”

A weak economic recovery is probably the reason some applicants are accepting jobs for which they are overqualified. Further, many individuals decided to get more education rather than seek a job during the worst years of the recession. It’s possible this trend has resulted in a job market that has more highly educated job seekers than in previous years. This can make it challenging for learning leaders to convince senior leaders to invest in learning to prepare for the future.

In addition to convincing employers that the future will require a greater investment in learning and employee education, employees and job seekers need to invest in their own learning. Here too, there are challenges. Notably, the survey identified a few industries that still have some jobs with no minimum education requirements, such as nonprofessional services (21 percent), construction, mining, oil and gas (19 percent), and manufacturing (12 percent). However, in all other industries, fewer than 10 percent of job openings had no minimum educational requirements.

Overall, 87 percent of organizations reported that employees with a high school diploma or equivalent are eligible for promotion at least some of the time, so some employees may feel they can avoid additional education and still advance. However, the scope of advancement for these workers appears to be limited. Promotions to an hourly supervisor or team lead position (43 percent) and one-step promotions (39 percent) are the most common career paths available for such employees, and ability to advance with no more than a high school diploma varies across industries.

A key task for CLOs in preparing for the future will be helping their organizations identify which job categories they will need to focus on most in their current and future learning investments. The type and cost of additional education that employees at various job levels need to advance varies based on job category. For low-skilled labor, skilled labor and administrative or secretarial jobs, the learning investment may be lower because it tends to be job-specific. But the investment may be much greater for an organization that has trouble filling jobs in the salaried individual contributors/professionals and managers category because here more than half of HR professionals say these workers need a bachelor’s degree or above to advance (Figure 2).

Employees themselves will be motivated to obtain more education if they believe it will help them advance. But the ongoing rise in education costs could make obtaining the needed degrees difficult. SHRM’s annual employee benefits surveys have shown a trend away from educational reimbursement as an employee benefit. Yet it is difficult to imagine a way to encourage more employees to obtain additional educational qualifications without at least some financial assistance. At minimum, employers will need to allow for greater workplace flexibility so employees can better manage their time between work and education.

What Minimum Education Will Soon Mean

Looking at the survey findings more closely, some of the biggest expected changes in projected educational requirements are in job categories such as skilled labor and administrative and secretarial positions. Across industries, 31 percent of organizations forecast the need for postsecondary certificates or credentials for future skilled labor positions, compared with 26 percent of organizations whose current workers in those jobs hold such qualifications.

Organizations are forecasting a much higher need for job candidates with associate degrees in administrative and secretarial jobs: 21 percent for future workers, compared with 12 percent with such degrees in the current workforce.

Even lower-skilled jobs will be more likely to have minimum education requirements in the future. Roughly seven out of 10 organizations are forecasting a requirement for a high school diploma, and 7 percent expect a specific postsecondary certificate or credential or an associate degree for such jobs.

Most organizations across industries project future educational requirements for salaried individual contributors and professional jobs to level off at bachelor’s degrees (71 percent), with only 5 percent forecasting requirements for advanced degrees for these types of jobs. However, some industries, including the federal government (26 percent), health (20 percent), professional services (23 percent), and state and local government (17 percent), are forecasting an increased need for advanced degree holders in management jobs.

The survey found organizations across industries are also projecting an increased need for advanced degree holders for future executive positions. Nearly one-half (48 percent) said they will have this requirement for future executives, compared with 38 percent who report current executive-level positions have advanced degrees as a minimum education requirement.

Budgets, Resources and Strategies

With so many organizations projecting the need for more skilled and educated workers in the future, the survey examined if this projection would translate into a bigger learning investment. While most organizations (57 percent) said they did have a training budget, a fairly sizable minority did not, and there was variation between industries. The majority (81 percent) of employees are trained on site, followed by employer-provided off-site training (57 percent), and training at technical or community colleges (44 percent).

The survey findings outline some key challenges for learning professionals. First, they must convince their organizational leaders that employee education is a priority. They must identify what their workforce needs are likely to be in the years ahead and what implications this may have for learning investments. Increasingly, they will need to become more involved in their local education environments to help develop a talent pool that has the needed skills, certifications and education going into the job, even while they must be prepared to help existing employees obtain the education they need while they work.

In the coming years, learning leaders will become even more central to their organizations’ strategies for success, but their jobs will not be easy. The challenges in convincing organizations to invest in learning are significant, but the evidence from the SHRM and Achieve research suggests the need for both will be even greater down the line.

Tanya A. Mulvey is a researcher in the SHRM Survey Research Center, and Jennifer Schramm is the manager of workforce trends and forecasting at SHRM. They can be reached at editor@CLOmedia.com.