When companies evaluate the broad array of management development tools and resources available, they turn increasingly to coaching for its flexible and highly personalized approach to enhancing leaders’ performance. Yet, despite growing popularity and broad acceptance of coaching, uncertainty persists with respect to its objectives, delivery and effectiveness.

First, there is some ambiguity about the differences between coaching, executive coaching and counseling. Adding to the confusion, coaching frequently suffers from a lack of transparency, organizational support and clear objectives, along with inadequate measurement, which impedes organizations’ ability to evaluate its effectiveness.

Further, different types of coaching will have different outcomes. General performance-based coaching is what managers and peers provide to individuals at any level on an ongoing basis. This type of coaching is tactical and is sometimes combined with counseling to fix a problem or improve a specific skill.

Executive coaching, on the other hand, is directly linked to a senior leader’s strategic growth achievement. It focuses on changing behavior to improve performance and to help senior leaders execute strategies that will deliver a specific result, as well as the organizational impact if the result is not achieved. The link between the two is that each aims to change behavior.

The essence of coaching is establishing a committed partnership between all stakeholders — the manager, the coachee, coach and HR — to deliver desired results.

Coaching for Leaders

Talent management adviser AMA Enterprise (Editor’s note: The author works for AMA Enterprise) conducted a national survey of more than 230 respondents in August to explore the policies and practices associated with executive coaching and its perceived value. The survey population consisted primarily of senior-level business, human resources and management professionals.

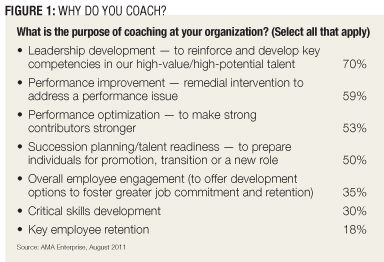

The survey, “Casting a Critical Eye on Coaching,” found that coaching is widely used. Forty-two percent of respondents provide coaching to anyone at any level in the organization, depending on need. However, individuals at mid- to senior levels are most likely (41 percent) to receive coaching. Seventeen percent of respondents only provide coaching to senior-level staff. Leadership development is the main purpose for executive coaching (Figure 1).

Because non-mandatory coaching competes with other claims on an employee’s time, it is imperative that engagements be designed to positively impact an employee’s work performance. Well-designed engagements are viewed by 35 percent of the survey participants as more valuable than other development methods, such as on-the-job training, workshops, formal courses, stretch assignments and functional training.

Coaching today is more about development than remedying problems, and savvy self-starters at the middle level see coaching as key to their advancement. Indeed, coaching’s growing popularity may be attributed to the fact that many perceive it as a perk earned by high-potential managers, with as many as 44 percent of respondents stating such.

Practices for Effective Engagements

AMA Enterprise recommends a six-step process for effective executive coaching engagements:

1. Business need evaluation: Identify the results and business impact the coaching engagement will deliver.

2. Engagement scope, strategy and approach: Assess and match a coach to the assignment.

3. Coachee assessment: A 360 with stakeholders will clarify what a leader does well and what he or she could do better. This involves feedback to align the leader, involves his/her manager and HR on the goals for the engagement and usually focuses on one to two key growth opportunities, such as listening skills or building strong cross-functional partnerships, for a period of about six months.

4. Goal setting/action planning: Create a tangible, step-by-step plan.

5. Coaching engagement delivery: This involves regular coaching, for 30 minutes weekly, 60 minutes monthly, but never less frequently than once every three weeks. More frequent sessions contribute to effectiveness.

6. Evaluation and measurement: Determine progress, reporting, impact analysis and continued development planning.

“I worked with a leader who was recognized as a high-potential employee. He was a strong performer, but feedback indicated he didn’t have the illustrious ‘executive presence’ expected in his position,” said Eileen Garger, vice president of strategic client partnerships at BlessingWhite, a global leadership consulting firm. “We implemented a 360-degree feedback tool which provided specific evidence of what he needed to change.

“He had been assigned to lead a major project with high visibility throughout the organization, and perception was that he was not in control of the interdepartmental meetings. We identified that one of the key milestones he needed to achieve involved building individual relationships with team members for them to get to know him and vice versa. We distilled the big idea of ‘executive presence’ down to tangible pieces and worked together through regular coaching sessions to achieve these goals. We developed action steps and measurable milestones. If these aren’t in place, coaching becomes a luxury that an organization just can’t afford.”

Coaching is also most effective when an organization’s culture supports it as a productive developmental initiative in an atmosphere of learning and shared relationships where information and ideas flow easily to points of greatest utility. Organizations need to avoid situations where knowledge is hoarded, activities are compartmentalized, silos are the norm and people are competitive and motivated only by self-interest.

“It’s commonly understood that many senior leaders today have coaches,” said Stephen Sass, managing partner and COO of CoachSource LLC, a global, virtual coaching firm. “When a CEO stands up on stage and says to the employee group ‘let me share what my coach and I have been working on,’ then it becomes culturally acceptable in the organization. Even a perk, perhaps.”

AMA Enterprise research found that coaching is usually kept secret at as many as two-thirds of organizations and sometimes secret at one-quarter. Companies should undertake coaching engagements with tact, transparency and an eye toward assuring talent that the process will be beneficial to career progress and drive performance. “An effective leader who has benefited from coaching will drive the engagement of other leaders and employees throughout the firm. And that only lends itself to positive bottom-line improvement,” Garger said.

Brian Underhill, CEO and founder of CoachSource, agreed that coaching engagements work best when the culture is favorable toward developing, improving and getting better. “Leaders are open to accepting feedback and having honest conversations, and there is a strong level of trust amongst the top executives,” he said. “This sets the overall tone for the whole organization.”

Watch for Derailers

Despite its wide use in corporate America, coaching gets mixed grades on performance. Just one-quarter of organizations that provide coaching have found it very effective and nearly two-thirds regard it as only somewhat effective, according to AMA Enterprise’s research. Further, 12 percent consider it ineffective.

According to Sass, coaching interventions cannot be effective when the leader is not serious and committed to the initiative. “What we tend to receive in these scenarios is lip service where the executive does not follow up on planned actions and meetings are frequently canceled and moved around. The individual leader really has to feel the need for the coaching to be personally engaged.”

Mixed grades for coaching are not dissimilar to those for other forms of executive and leadership development, however. So a critical assessment of coaching should not be a cause for alarm, but a reminder that measurement and accountability may never be taken for granted. “We implement a 360 assessment at the start of the engagement so we have a benchmark,” Sass said. “Then about six months later we administer a similar assessment so we can gauge if we are moving the meter in the right direction with the executive and for the right behaviors. We use this to determine that the individual is learning and applying behavioral change and whether or not this change is positively impacting the business.”

Compared with other development tools such as on-the-job training, workshops, formal courses, stretch assignments and functional training, coaching delivers a measurable business impact more often than other initiatives 35 percent of the time, according to AMA Enterprise research. Respondents also said coaching has impact as often as other initiatives 37 percent of the time. Only 28 percent said it delivered impact less often (Figure 2).

The most common difficulties involved with coaching are conflicting priorities and time constraints, lack of sponsor/manager support, lack of resources to provide the coaching and difficulty assessing its effectiveness.

Underhill said another common derailer is that coaching may not be for everyone. “Executive coaching can’t succeed when it is pushed on an individual as a last resort to save someone who already has one foot out the door,” he said. “I once had a boss suggest to me “let’s throw a coach at the problem and see if that will work.” Well, in short — it doesn’t. As coaches, we make good leaders even better and accelerate their development and contribution. We don’t save poor leaders.

“When the person being coached starts to argue with you and defend themselves, it’s clear that they aren’t buying into this and that the true reasons for the engagement were not articulated nor understood.”

Coaching likely will continue to expand as a preferred leadership development practice. It will remain an essential initiative to develop and retain scarce talent, and companies will continue to leverage coaching to compete in the global marketplace.

Sandi Edwards is senior vice president at AMA Enterprise, a division of American Management Association that offers advisory services and tailored learning programs. She can be reached at editor@CLOmedia.com.