Significant foundational skills gaps exist for many current and potential U.S. workers, according to a report issued by nonprofit educational association ACT. (Editor’s note: The author works for ACT). The report investigates the assumption that individuals with a specific level of education have the skills needed by occupations requiring that level of education.

Based on workplace skills data collected from approximately 4 million workplace assessment examinees over a five-year period, the report, “The Condition of Work Readiness in the United States,” finds that skills gaps are most evident for individuals considering jobs requiring low or high levels of education. In contrast, there is no significant skills gap for individuals preparing for jobs that require middle-level education.

These findings suggest that institutions and programs preparing individuals for middle-education jobs — those requiring at least one but less than four years of formal training beyond high school — are well aligned with the skills those jobs demand. As a result, hiring and learning professionals tasked with selecting and developing America’s workers should be cautious when considering indirect measures like education level as a proxy for actual skill levels required on the job.

For about two decades, educators, employers and workforce development personnel have been using ACT WorkKeys workplace skills assessments. Based on data extracted from examinee scores from 2006 to 2011, ACT’s “Condition of Work Readiness,” published this year, highlights levels of work readiness and provides standards and benchmarks for targeted occupations during the next eight to 10 years.

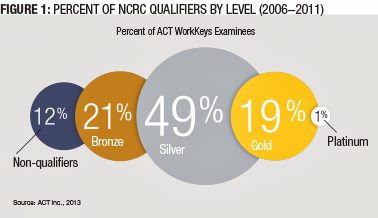

Figure 1 shows the distribution of scores for the approximately 4 million examinees who took three of the cognitive skills assessments: reading for information, applied mathematics and locating information. These three assessments form the basis of the ACT National Career Readiness Certificate, or NCRC, a credential that documents essential foundational skills consistently identified as important for success in a broad range of jobs.

Each assessment has a score range of either 3 to 6 or 3 to 7. The NCRC is awarded to individuals achieving a score of at least 3 on all three assessments. Four certificate levels are possible: bronze (minimum of 3 on all three assessments), silver (minimum of 4), gold (minimum of 5), or platinum (minimum of 6). Although 69 percent of the 2006-2011 examinees qualified for a silver level or higher, 21 percent qualified for the bronze (lowest) level. Further, 12 percent failed to qualify because they scored below 3 on at least one of the assessments.

Drilling down a step further, ACT researchers looked at performance as measured by skills assessments for individuals with different levels of education in three categories:

• High: Four years or more of formal training beyond high school.

• Middle: At least one but less than four years of formal training beyond high school.

• Low: No formal training beyond high school.

In Figure 2, 89 percent of examinees with a high level of education were likely to qualify for the NCRC at a silver level or higher, compared with 77 percent of examinees with a middle level of education or 65 percent of those with a low level.

Hidden Skills Gaps

ACT researchers examined 45 target occupations requiring each educational level and found that skills gaps are most evident for individuals considering target occupations requiring low or high levels of education. In contrast, there is no significant skills gap for individuals preparing for target occupations that require middle-level education.

Much has been written about the so-called middle-skills gap. Sometimes the term refers to a shortage of workers with a skill set suitable for jobs requiring middle-level preparation. For this study, researchers weren’t addressing a shortage of workers but a shortage of skills. The investigation focused on whether individuals with a certain level of postsecondary education or training were ready to succeed in target occupations requiring that level of preparation.

The findings suggest on the whole, institutions and programs preparing individuals for target middle-education occupations are well-aligned with the skills those jobs demand, while those preparing individuals for high- and low-education target occupations are less aligned with the skills those jobs demand.

How is it that individuals with a four-year degree or more could show a greater skills gap than those with less education? One part of the answer is that contextual workplace assessments demonstrate people’s actual workplace skills more accurately than educational attainment alone. Such assessments help determine work readiness.

An earlier ACT report, “Work Readiness Standards and Benchmarks,” also published this year, defined work readiness and recommended a methodology to precisely describe the knowledge and combination of skills individuals need to be minimally qualified for a specific occupation. In “Condition of Work Readiness,” researchers built on that definition and examined results regarding target occupations for each of the three education levels based on three criteria: fastest growing, most openings and highest paying.

Following are examples depicting each of the three education levels and job projection criteria:

High education level required/fast-growing field:

The accounting/auditing field, which requires a high education level, is projected to grow 16 percent from 2010 to 2020, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. With more than 450,000 anticipated openings in that 10-year period, the field is one of the fastest-growing occupations for individuals with a high education level.

ACT job analysis data established a median entry skill level for this occupation at Level 5 for all three foundational ACT WorkKeys assessments (Figure 3). Most highly educated examinees did well in reading for information and applied mathematics, but fewer than half (45 percent) met or exceeded the entry skill level for locating information.

Low education level required/high-paying field: Examinees with low levels of education tend to have an even greater deficiency of locating information skills than examinees with high levels of education. For instance, 4 of the 5 projected highest-paying occupations for low-education jobs in the 2010-2020 decade are:

• Tool and die makers.

• First-line supervisors of construction trade workers.

• First-line supervisors of mechanics, installers and repairers.

• Transportation, storage and distribution managers.

For all four of these occupations, the ratio of examinees meeting or exceeding the entry skill requirement in locating information was less than 1 in 5.

Middle education level required/fields with most openings: According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, projected openings for registered nurses will total 1.2 million by 2020. Work readiness benchmarks for this field show a 5 in reading for information and a 4 in applied mathematics and locating information. Of those tested, 74 percent met the reading benchmark and 85 percent and 84 percent met the mathematics and information benchmarks, respectively.

Although these could be improved, the readiness levels for this middle-education-level occupation are relatively good, indicating that preparation programs seem to be aligned with the foundational workplace skills needed.

Recommendations to Consider

The findings indicate that leaders should be cautious when considering indirect measures of skills, such as education level attained, as a proxy for actual skill level. While education is important, a more holistic view of an individual’s knowledge, skills, attitudes and personal characteristics should be considered when determining occupation fit.

Key conclusions from the data in the “Condition of Work Readiness” report include specific measures organizations can take to increase work readiness:

• Adopt strategies within education and workforce development systems to help individuals identify and address skills gaps relative to their career goals.

• Improve collaboration among educators, employers and industry leaders to develop authentic learning experiences along the continuum from K-12, postsecondary and career education.

• Improve alignment between education and workforce development efforts at the local, state and regional levels.

Employers, and more specifically learning professionals, are the eventual consumers of the education pipeline. If they are not speaking the same language as the educators who prepare tomorrow’s workers, those workers likely won’t be prepared to succeed. The first step is to be aware of needed skills and be able to communicate those needs in ways educators will understand. It’s one thing to say, “I need workers with better math skills.” It’s another to say, “I need an individual with at least a 5 in applied mathematics.” That’s possible if detailed task and skill analyses are performed for key positions. Setting specific benchmarks helps educators know how to better prepare students, and helps employers improve the return on every learning dollar invested.

One finding in the “Work Readiness Standards and Benchmarks” report is that mastery of core foundational skills empowers an individual to rise to the next tier within an occupation. Foundational skills include workplace skills that are portable across all occupations and that are fundamental to convey and receive information critical to training and workplace success.

National layered credentialing systems do exist to help employers create multiple avenues for individuals to advance along a career pathway. One such system is the Manufacturing Skills Certification System endorsed by the National Association of Manufacturers and illustrated in Figure 4. The figure shows the progression from foundational credentials, including those measured by ACT WorkKeys assessments, industry-wide credentials and specific occupational credentials. It is a system that is integrated across sectors horizontally and within sectors vertically. Adopting such a system adds value to workers’ lifelong earning potential and to an employer’s team of skilled workers.

Melissa Murer Corrigan is the interim head of the workforce development division at ACT Inc. She can be reached at editor@CLOmedia.com.

RESEARCH TAKEAWAYS

Key takeaways from ACT’s 2013 research report “The Condition of Work Readiness in the United States”:

• A higher level of education does not always guarantee work readiness. Completing required postsecondary education may not equip individuals

with the skills jobs demand.

• The ability to locate information from graphical presentations is a foundational skill that most individuals lack, more so than reading comprehension or workplace mathematics skills.

• Programs preparing individuals for middle education jobs seem to be better aligned with the skills those jobs demand than those at either end of the education spectrum.

• Be cautious when considering indirect measures of skills as a proxy for actual skill levels. Detailed job analyses can help define the skills and skill levels required for success. Hiring and training curricula can then be identified to build relevant skills on a career path that benefits the worker, the team and the organization as a whole.